Tracing Country Music’s Close Calls with Lyrical and Musical Complexity

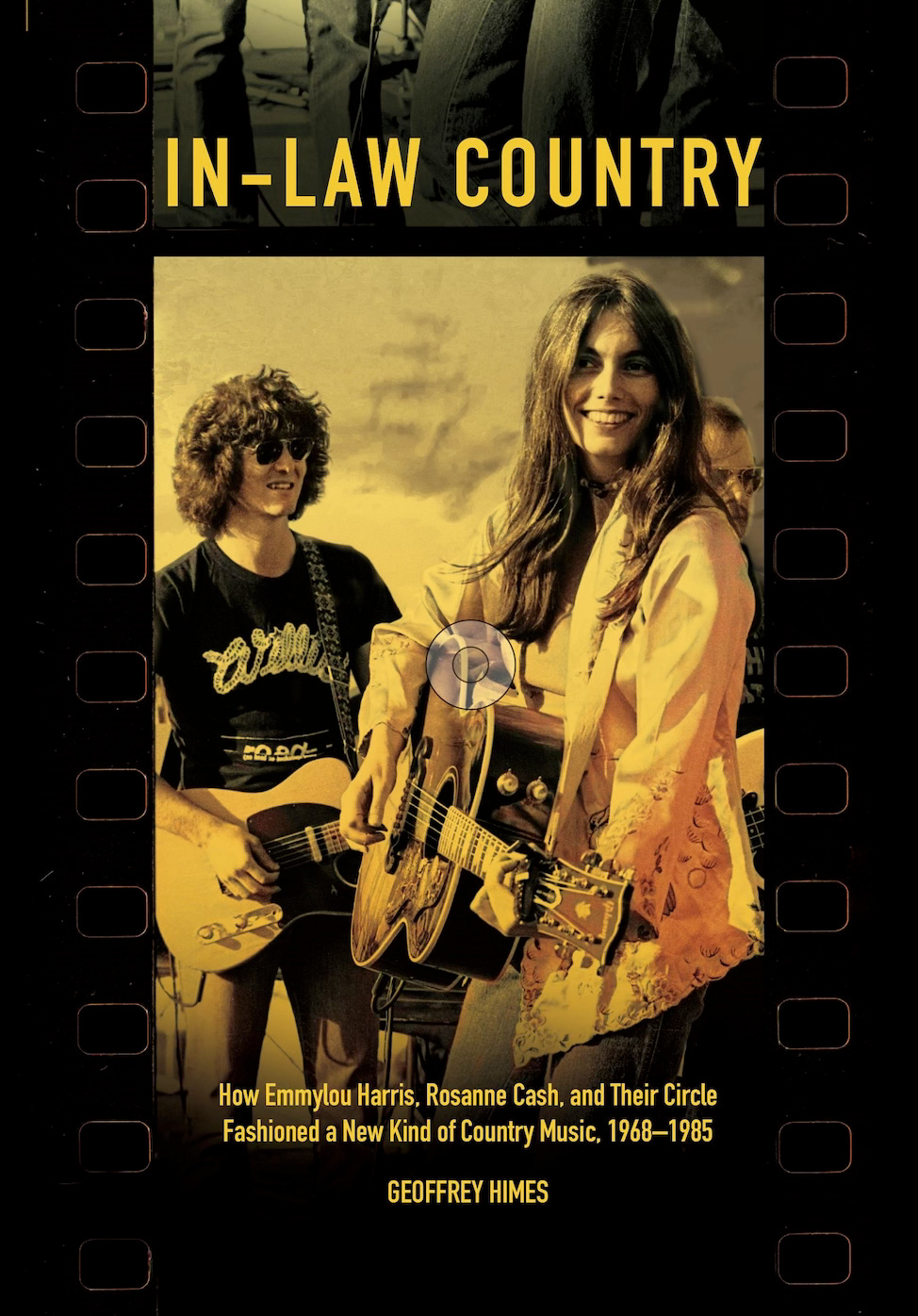

Rosanne Cash & Emmylou Harris’s Lasting Influence Documented in New Book, "In-Law Country"

As a gay ‘90s kid obsessed with the women of country music, I was drawn to the idiosyncrasies and intimacies I heard in the songs written and/or recorded by fascinating artists like Mary Chapin Carpenter, Pam Tillis, Trisha Yearwood, Patty Loveless, Kathy Mattea, K.T. Oslin, and, of course, The Judds.

By the time I came to country music as an obsession in 1992, thanks to my first Garth Brooks & Martina McBride concert, Rosanne Cash and Emmylou Harris were already over in alt-country territory, which would soon become known as Americana. Though it seems like some kind of utopian dream here in 2025, Emmylou and Rosanne really did have a run of mainstream country hits, as the ‘70s gave way to the ‘80s, that paved the way for those complex lyrical and musical presentations I heard from the women of ‘90s country.

Journalist Geoffrey Himes’ new book, In-Law Country, offers a deep dive on the hit records Rosanne and Emmylou’s racked up, on their own terms, while looking at the family relations by marriage, and sometimes divorce, that tied their careers to the Rodney Crowell, producer Brian Ahern, Ricky Skaggs & Sharon White, Guy & Susanna Clark, and Townes Van Zandt. It’s a vital period in country music that often gets glossed over since it took place in the same period the Urban Cowboy/pop crossover craze of the late ‘70s gave way to the Neo-Traditional movement of the mid-‘80s.

Here’s my conversation with Geoffrey, edited for content and clarity:

Hunter Kelly: I love that you center Emmylou Harris and Rosanne Cash in the the subtitle, but In-Law Country is really based on the work and lives of Emmylou, Rosanne Cash, Rodney Crowell, Ricky Skaggs, Guy Clark, and kind of going out from there.

These are really literary, progressive musicians making country music. What throughline did you see in their music?

Geoffrey Himes: I was fascinated by several things. I was fascinated by all the connections. Ricky and Rodney worked for Emmylou. Guy and Rodney wrote for Emmylou. I was also fascinated that they were able to take sort of very hip, literary songs and have country hits with them, which seems so implausible today. And they were able to do that in a way that the Byrds and Gram Parsons were not able to do with their music. I recognize that these are not just a random assortment of individual artists, but there was a real movement here that tied together in a lot of ways.

I interviewed Rosanne once and she said, “I never listened to country music when I was a kid. I listened to my dad, of course, but that was just my dad. I mostly listened to Tom Petty, Fleetwood Mac. And then I grew up, I got my heart broken, I said, ‘Oh my God, this music makes perfect sense.’”

And then she said this really key line. She said, "You know, rock and roll is dating music, and country music is marriage music. And it's about adult relationships and trying to hold them together against challenges inside and outside the relationship.”

One thing that's characteristic of the people I write about in this book is that they're writing marriage music, but it's marriage music that's for a new kind of marriage. The baby boomers weren’t willing to have a hierarchical marriage that had been so conventional, especially in the rural South. In this new kind of marriage, the husband and wife were more equal partners and required a whole different kind of negotiation and working things out in the marriage. That, in turn, required a new kind of song, and these people were supplying those songs.

HK: Rosanne Cash And Rodney Crowell were writing song about their marriage in real time. Especially from Rosanne's point of view, what female perspective did she bring to country music that hadn't been represented before?

GH: It’s that sort of a new kind of marriage where she was willing to compromise, but she wasn't willing to surrender. And she wasn't going to pretend that she didn't have romantic, sexual desire of her own. She wasn't going to be the virginal wife, which is a nutty kind of thing to imagine.

She wasn't willing to give up on men, like some people of that era were. She wanted a marriage; she wanted children; but she wanted it on her terms. And, you know, I think that comes through in her songs.

And she was always very conflicted about having a career that took her away from her family as much as it did, because she had grown up in a family where that was a very damaging dynamic that wrecked her parents’ marriage.

She sang that song of Rodney's called “Ain't No Money.” It's like, there's no money in staying home, but you don't want to lose home to chase the money.

HK: Another hallmark of “In-Law Country” is the artists’ ambivalence represented in the lyrics and the music. There is a hesitancy to jump to any easy conclusions. Where did that come from?

GH: They came up in a time where assumptions about the way things should be were being questioned. Just because the government said it, or the church said it, or your parents said it, doesn’t mean that it was right or wrong. It means that you had to figure out what you believed in for yourself.

Once you approach life that way, there's usually a gap between the way things should be and the way things are, whether it's your marriage or your career or your government or whatever. Being able to hold both those ideas in your head is how I describe irony. Dylan and Lennon and those guys were masters of that. And these people grew up listening to that music. And so when they wrote songs, that inevitably came out.

HK: And that ambivalence showed up in the harmonic structures as well, if we look at a song like Emmylou Harris’s recording of Rodney Crowell’s “Till I Gain Control Again.” How did they convey that emotional complexity in the chord structures and production choices?

GH: It's that element of surprise or unpredictability in this music so that you don't know where it's going — in the same way that you don't know where your life is going, or you don't know what the obvious answer to your questions are.

Rodney would talk to me about using minor sixth and major sevenths and things that aren't avant-garde, but they weren't part of the conventional country vocabulary in those days. Listeners don't understand music theory that to that level, but they can feel that there's something different going on in the music — that this is not about being sure of what your world is like, but it's being ambivalent about what the world is like. They were taking a lot of lessons from the vanguard of rock and roll, like the Beatles and The Byrds and Dylan and Paul Simon and applying it to country music and applying it to marriage music.

You know, even though Rosanne grew up in California, she was Johnny Cash's daughter. So, they all had country backgrounds. Guy Clark, Steve Earle, Townes Van Zandt and Rodney are all from Texas. You know, Emmy was an army brat and bounced around all over the country. So, when they made music, they wanted to make music for people of the same background. I think that's why they made country music rather than rock and roll.

HK: I want to nerd out a little bit on the work of Brian Ahern. You really hone in on Brian's production techniques on Emmylou's early Warner Brothers albums. He had come from working with Anne Murray, and his recording expertise made those records stand above what had happened before in Country Rock. So, what was it that Brian brought that made the difference?

GH: When Brian was recruited from Canada by Mary Martin to work with Emmy, he had learned a lot of the basics of his craft working with Anne Murray, but he sort of felt he had hit a wall and there were a lot of things he wanted to try that he couldn't try with her.

Emmy was just starting out. She’d made one really terrible album, which was a folky project, Gliding Bird. She disavows it so much that she titled her 14th album, Thirteen. So, they're both sort of starting with a clean slate when they started working together.

Brian did several things. First of all, he refused to do the sort of country thing of knocking out three songs in a three-hour session. He wanted to do the more rock and roll thing of taking your time and making it sound really good, whether it's a single or an album cut.

And he also wanted to make country instruments heard again in country music. It’s not only that he used fiddle and mandolin and acoustic guitar a lot, but he brought them up in the mix where he could hear them. So, they were co-equal with the drums and bass and electric guitar. That was important.

To make sure the things he wanted got heard, he cleared out a lot of the clutter in the arrangements. There wasn’t a lot of high hat or constantly strumming guitar. You listen to those records, and they're very lucid. There's space in them that you can hear the voice. You could hear the key instruments. People will step forward and do a little figure and then step back again. So, it was a new sound. It was very clean in a way that worked on radio in a way that Gram Parsons’ songs didn't work on radio, or country radio especially, because they were about energy and just going for it without structure and clarity. That's a big reason why Emmy’s songs became hits and Gram’s didn't.

What's also interesting is that people that Brian worked with in the studio, which includes Rodney and Ricky Skaggs and Emory Gordy and Tony Brown, all went on to become major country music producers. Like we say in football, there's a coaching tree where the branches come off the trunk. Well, in country, there was a Brian Ahern tree with all these branches coming off of them.

HK: Emmylou and Brian were making these records in Los Angeles. Having operated in Nashville for 24 years as I did I know that when an outsider comes in, they have to jump through hoops to prove they belong in country music. How did Emmylou overcome that gatekeeping aspect?

GH: Well, in one sense, being in California gave them enough distance that they could experiment and come up with a sound on their own without a lot of suits looking over the shoulder the whole time. And they made records that were sort of undeniable. They were so beautiful.

She has said in interviews that she knew there was a lot of skepticism about her really being country since she had sung Beatles songs on those early albums. That’s why she did Blue Kentucky Girl with all the Loretta Lynn songs and then the Bluegrass albums. She said, “Well, I'll show you I can do this as well as anybody.”

And then from 1979 to 1981, they all moved back to Nashville — Rodney and Rosanne came back, Emory and Patty [Loveless] moved back. Hank DeVito moved back. Tony Brown came back, and so it's sort of all relocated in Nashville. And then they were sort of in the center of it again. But at that point, they had hits under their belt, so they had some leverage.

HK: Well, these are the people who made country music in Nashville interesting. For me, the key is looking at how these artists got that autonomy. My hope is that this is a kind of a game plan or encouragement for people even today, because I still find that my interest in mainstream country music only goes so far as what's messing it up and what's really muddying the waters — or really, how much Americana can we get into mainstream country?

And it seems like that divide between country and Americana has gotten wider and wider, or that wall between hem has gotten more impenetrable.

GH: One thing that sort of struck me in this century is that those Americana people are able to top the country album charts, but not the singles charts. They’re able to sell out the Ryman, but they still can't get on country radio. I think there's a weird business thing going on, but I think that spirit is still alive. You look at Jason Isbell and Amanda Shires, or Buddy and Julie Miller, or Jeremy Ivey and Margo Price — there’s still that dynamic of musician couples writing about marriage music in sort of interesting, smart ways. So that hasn't really gone away. What's gone away in a sense is their access to country radio, which is a problem. I'm not sure what the solution is.

HK: One of the people that I really learned a lot about was the late guitarist, Clarence White, who came up with the group, the Kentucky Colonels and played with The Byrds. What did Clarence bring to the conversation as far as introducing the acoustic guitar as a lead instrument in bluegrass, and how did that bleed into country?

GH: Clarence and his brothers, Roland White, who was in the Nashville Bluegrass Band for many years, and Eric White, who was also a musician, they grew up in Maine and spoke French at home. Their original names was LeBlanc, but then they played sort of Celtic folk music — Quebecois music. And then they moved to California, and they got hooked on bluegrass first.

Once Clarence figured out how to individually mic his guitar, he became one of the first people to play lead acoustic guitar in bluegrass. Doc Watson did, but he was sort of a solo act. Tony Rice says it was mind blowing for somebody like him to hear Clarence.

Clarence was fast, but more importantly, he was musical. When he transferred that to a Telecaster, it fit right into that tradition of James Burton and Don Rich and those Bakersfield guys. There was a real respect for virtuosity and for giving instrumentalists their chance to shine.

It was not just Clarence, but those records that are covered in In-Law Country featured major pickers and players like Ricky Skaggs and Sam Bush and Bela Fleck and Mark O'Connor. They played really well, and you could hear them because Brian made sure that those guys got heard.

HK: Another concept in this book that really resonated with me was the idea of creating a musical revolution by going back in time, which Emmylou did with Roses in the Snow. In that spirit, I want to go back farther to Bill Monroe and the way that he arranged bluegrass music. You touch on how it was inspired by the virtuosity he heard on the radio in jazz music. I'm fascinated by the cross pollination going on there.

GH: In the '30s, suddenly, there were radios in those little hollers in Kentucky, and you weren't just hearing the local hotshot violin player. You could hear Benny Goodman. You could hear Tex Ritter. You could hear all these people who can really play.

And the trains were coming, and electricity was coming. It was like the modern world had finally reached into those obscure little coal mining communities and dirt farms in West Texas or Alabama. And people were excited. They wanted to play faster. They wanted to play louder, and I think that that's what got to Bill.

He started out in a sort of more conventional brother duet kind of thing with his brother, Charlie. But he heard this other sound. When he found Earl Scruggs, he found someone who could play the sound that was in his head. And it was revolutionary.

What was fascinating to me about Bill Monroe, and about Ricky Skaggs, at the same time is that they were very religious, very conservative people in their lives. But as musicians, they were wild radicals. And people don't realize how strange and exciting Monroe was. When Ricky started playing those things on country radio in the early '80s, a whole new generation just went nuts. They hadn't heard anything like that since The Beverly Hillbillies.

HK: Rodney Crowell left Emmylou's band in the late ‘70s, and Ricky Skaggs came in. You write that Ricky had made a promise to himself to only join bands that featured harmony singing where his voice would be used. So, joining Emmylou’s band was a perfect opportunity. What did Ricky bring to those Emmylou records, especially Roses in the Snow, that wasn't there before?

GH: Well, Roses in the Snow and Light of the Stable, which is probably one of the greatest country Christmas albums ever made, basically were the same sessions. Emmy and Brian wanted to do a bluegrass record, because they loved to listen to that music. But they needed an insider who knew that vocabulary and how it was put together. And that was Ricky's role. He worked with Brian pretty closely on the arrangements and the mixes to make sure that they got the sound right.

Ricky learned a lot that he didn't know about songwriting and about using a rhythm section, which is is working with drums and electric bass. That was new to him. So, both sides got a lot out of it.

HK: When we're talking about the acoustic guitar as a voice on records, I think about Ricky’s solo records that were such big hits in the early ‘80s, like “Country Boy,” “Uncle Penn.”

GH: And a Guy Clark song, “Heartbroke.”

HK: “Heartbroke,” which I knew first as a George Strait song on his box set. I think there was some kerfuffle when George Strait opened for Ricky Skaggs and he played “Heartbroke” and that was supposed to be Ricky’s latest single, anyway. Early ‘80s country drama.

You said that Ricky was adamant that bluegrass had to change and evolve and be radical. So, he brought in that low-end on the records. I’m thinking about “Honey (Open That Door)” with the fat sounds on the bass and drums.

GH: Ricky has always been adamant that those records he made on Epic are not bluegrass. That they’re bluegrass-flavored country music, and he always made a distinction between those records and his bluegrass records. There's definitely overlap, but he always thought of them as different things.

He came up with the sound, borrowing a lot from Brian. That mix of bluegrass with the rhythm section was unprecedented. The Osborne Brothers did something very similar, but he really perfected it in a way that gave him a lot of hits — a lot more hits than any other bluegrass guy had.

Eventually, it wore out its welcome, like all things do.

HK: Yeah, it was really interesting to trace that because, with The Judds’ music being acoustic, I realized that by the time they had their audition with RCA in 1983, the idea of them doing acoustic-based music with these harmonies was not that far-fetched. Ricky was on his fourth or fifth number one in a row when they got signed.

Going back and listening to Ricky do “So Round, So Firm, So Fully Packed,” there are sexual innuendos going on there that totally went away as Ricky got more up front about his Christian faith. You make the case that it watered water down Ricky's music and made it less effective because he avoided topics like cheating and drinking?

GH: I think it made it hard for him to deal with certain issues and conflicts in marriages, like temptation and drinking and cheating. We don't have to approve of those activities to enjoy hearing about them in music, you know.

We're all, we're all flawed human beings. Maybe not you, Hunter, but most of us are.

HK: No, I can admit that I am flawed.

And I admit that I have been intimidated by Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark for a long time, just because I think they're kind of these Mount Rushmore figures of songwriting. They can be a little inscrutable, especially Townes.

But this book humanized Townes Van Zandt for me in such a profound way that really opened up his music for me. I’ve got to say, some of his pessimism, or just that idea that things aren't going to be better, is really resonating with me in this year, 2024. I'm like, “Yes, Townes, I hear you.”

I think when people look at Townes, who is an artist who has a lot of name recognition and his songwriting is so influential, but he never really had a hit record of his own that you can go listen to.

GH: Well, not a hit record that he sang.

HK: Yes. That HE sang. So, as far as listening to Townes, where should people start?

GH: Well, let's just start with Merle and Willie's version of “Pancho and Lefty.” Or Emmylou's “If I Needed You” with Don Williams.

My favorite Townes record is Live at the Old Quarter in Houston, which is a live, coffeehouse record. It’s very early when he was still in pretty good shape. There's a sort of a rare record which has Guy and Steve Earle and Townes, and Emmy comes in for a little bit, at the Bluebird Cafe in Nashville. It's a brilliant record. They’re all three trying to top each other, and they're all giving Steve a hard time. It's a wonderful record. So those are two really good entry points.

This is another interesting thing about the “In-Law” people is that, unlike Townes, Steve and Guy wanted to have careers. Emmylou and Rosanne wanted to have careers. They wanted to get on the radio. They wanted people to hear them, and Townes was happy just writing great songs. He didn't have that other ambition you really need to have in this industry to crack it open.

HK: The relationship between Townes and then Guy Clark and Susanna Clark is such a unique, but rich intersection for songwriting and the craft of songwriting. I love what you said about Guy really working on his songs over time and having a real workman quality to it. He didn’t buy into that idea that songwriting is just tapping into channeling some spirit when you’re writing songs.

Geoffrey: You know, there was that period, which I described in the book, where Guy and Townes would hold court in Guy's house or John Lomax's house or Bishop’s Pub. No one had much money. All of them were trying to get better and better at what they did, and they would get together and drink and talk, and then eventually the guitars would come out and everybody would sing their latest song. Steve and Rodney especially were part of that scene, and it was like going to graduate school in songwriting.

Steve and Rodney both told me that, what was weird about it was that it wasn't about who had the latest cut. It was about who had written the best song, and who had done the best work. It instilled a measuring stick in their heads that they never lost for the rest of their lives.

HK: Why was 1985 the cutoff year for this book?

GH: Well, because I wrote a huge book, and they only published the first half of it.

HK: So, the second half is written?

GH: In rough draft, yeah. So that's why it's important that everybody go out and buy this one so that they’ll publish the second volume.

In-Law Country is released in collaboration with The Country Music Hall of Fame and distributed by University of Illinois Press. Geoffrey Himes will appear in-person for a Q&A on In-Law Country at the Hall of Fame February 22 . You can get your tickets here.

Hi Geoffrey! Look forward to the book xo Thanks for covering this Hunter.